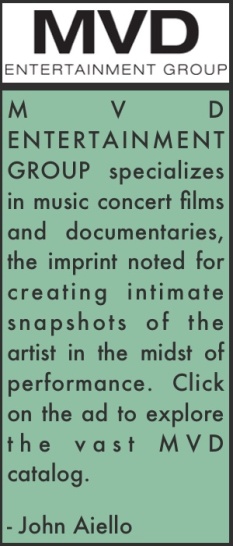

The Complete Budokan 1978 Shows Us Everything A Live Record Can Be

BOB DYLAN – THE COMPLETE BUDOKAN 1978. Bob Dylan. Produced by Tetsuya Shiroki with Heckel Sugano; chief engineer/remix Tom Suzuki. Liner notes by Edna Gundersen. Bob Dylan At Budokan originally produced by Don DeVito. Sony Legacy.

In 1978, Bob Dylan toured Japan for the first time in his career. The shows he played at the Budokan Hall were unlike anything we’d ever heard from him before: Instead of the classic 5 man band he customarily fronted, he was now flanked by an 11-person ensemble that featured the great Steve Douglas on saxophone and Billy Cross on lead guitar.

1978 was a true period of transition for Dylan on multiple planes. Musically, he was setting off to explore Phil Spector’s classic ‘wall of sound.’ And the band that Dylan stitched together in search of the rhythm he heard in his head was perfect for the task – the feel big and bold, teeming with layers. Moreover, the once hollow ache of his voice was suddenly clear and taut and sinewy, sprawling across the four corners of the room like a boa constrictor broken free of its cage.

The Complete Budokan 1978 vibrantly recreates the sound that Dylan toyed with for only a short time as memorialized on Street Legal and the original Bob Dylan at Budokan album. Interestingly, even though Street Legal was released in 1978 before the Bob Dylan at Budokan album, it was actually cut four months after the mid-winter Japan tour. At the time, the records left throngs of Dylan’s old fans confused: Most were expecting the denim-clad Dylan of Rolling Thunder, and what they got was a man-about-stage performer decked out in Elvis’ threads with a band that had enough juice to blow the Stones off stage.

In essence, The Complete Budokan 1978 is what the original concert recording wanted to be. This marks a spectacular effort on the part of Sony’s engineers as they enriched, enlarged and emboldened the clarity of the original Budokan – whetting a brand new record from the old masters. Now, we’re better able to hear the way the band drove Dylan to find new pieces of himself in his old songs. These shows punch with energy, urgency and grace – a riveting performance completely encompassing the first 15 years of Dylan’s storied career.

Many will call this a ‘reissue,’ but in point of fact a great deal of this music hasn’t been heard before. The 4-CD box, recorded February 28 and March 1, 1978 at Japan’s Nippon Budokan Hall, includes 36 previously unreleased tracks; unsurprisingly, these songs prove the most compelling.

Specifically, the inter-play between Douglas and Cross throughout the record is amazing, but it truly shines on both versions of “Like A Rolling Stone” – collectively, these are the second best live versions of the song we have (the best is from 1966 with Robbie Robertson and the Hawks providing the electric lines). Meanwhile, Dylan’s voice also has never been in better form than what we hear in “Girl From The North Country,” “Repossession Blues,” “Oh Sister,” “Going, Going, Gone,” “Love Her With a Feeling,” “Just Like a Woman” (second night) and “It’s Alright Ma.” These versions of “Ramona” and “Tambourine Man” are also special – the warm razor-point lilt of each breathless and intoxicating.

But the one truly indispensable cut here is the March 1st version of “One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later),” the forgotten classic from the Blonde on Blonde sessions. Dylan’s performance here is what rock and roll is all about: bloody and thirsty and passionate, telling a story of tangled love and lost direction in Keatsian lines that leave both orator and audience spinning out of breath.

Other notable moments include Dylan’s impassioned harp solos on “Just Like a Woman” as well as Steve Douglas’ horn work on “Tomorrow is a Long Time” and the burning instrumental versions of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (where his sax actually impersonates Dylan’s voice). Douglas, along with Robbie Robertson, were the two best musicians with whom Dylan ever played. In turn, the saxophone lines recorded in full blistered bloom here make us wish Dylan and Douglas had collaborated more regularly through the years.

In the end, The Complete Budokan 1978 is the blueprint for what a live concert recording is meant to do – that being, to return us to a place in the past, returning time to a moment that had been laid away in a vault where all the keys were presumed lost.

Until today. The calendar says these recordings are some 45 years old. But they sound as fresh here as the dew trembling down the lips of your shoes.

End Notes

Budokan is by far the sharpest boxed package Dylan has ever released: The ‘memorabilia’ folder and the accompanying booklet comprised of liner notes and rare photos from the tour document just how dear this material is to the musician – a sparkling jewel in the crown of a legendary career. This review paints only a partial picture of album highlights. You should go and discover the rest of them for yourself.

Of Related Interest

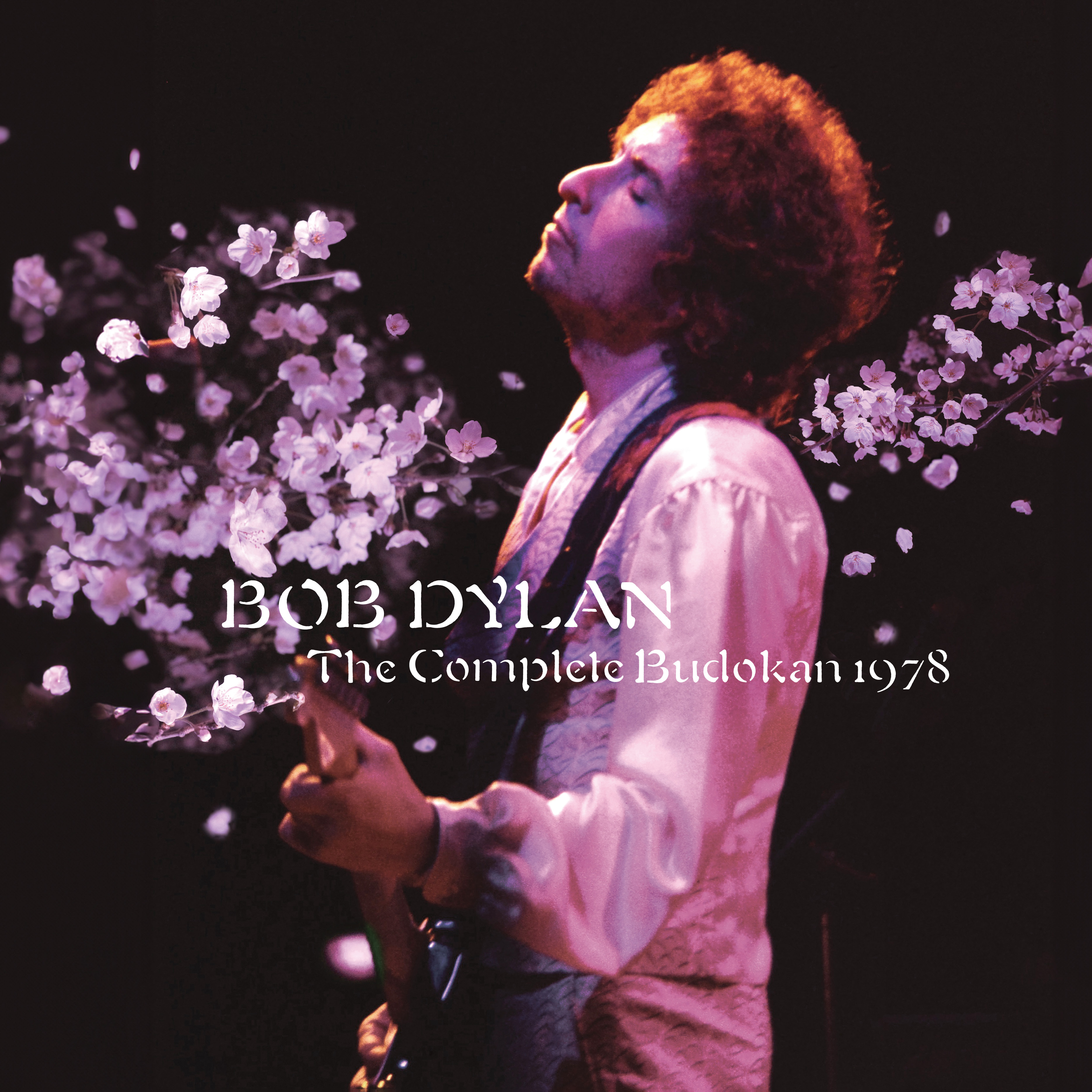

THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 17: FRAGMENTS – TIME OUT OF MIND SESSIONS (1996–1997). Bob Dylan. Produced for release by Jeff Rosen and Steve Berkowitz. Sony Legacy.

Released in January 2023, this installment of the famed Bootleg Series came along quietly and seemingly went by unnoticed. Which is strange, since Time Out of Mind marked Dylan’s comeback album from obscurity. Nevertheless, the five CD box includes some stunning out-takes from the the original Time sessions, including remixed classics “Not Dark Yet, ” “Cold Irons Bound” and “Highland.” Producers Jeff Rosen and Steve Berkowitz did an admirable job here in compiling a record that brings us music that is completely new in tone and texture while simultaneously staying true to the original spirit of the Time sessions. For example, the alternate version (1) of “Not Dark Yet” has been sped up and there’s a revamped “Queen Jane” mood to Dylan’s vocal, yet the song remains haunting in delivery and scope – a reportage of a world at war of a society drowning in internal conflict. Those fans who still want Dylan to rewrite “The Times They Are A-Changin” should give a long and serious listen to this record: In some respects, he’s painted a much more piercing portrait of our life and times than that he did in that 60’s masterpiece. I believe Sony Legacy issued The Complete Budokan 1978 and Fragments back-to-back purposely, since both of these records document a major transition phase and musical shift for Dylan. As such, the compilations should be listened to in sequence and allowed to naturally coalesce – a testament to Dylan’s perpetual growth as an artist. A testament to an artist unafraid to reinvent himself in the moment on the spot.

End Notes

The package also contains the original Time Out of Mind album which has been completely remixed, in addition to a CD that features live performances of each of the songs from the Grammy-winning 1997 release (except “Dirt Road Blues”). The live record offers a real time snapshot of the twists and turns of Dylan’s ‘Never Ending Tour,’ sharing some of the inspirations that still keep him on the road after 60-plus years. In the end, Rosen and Berkowitz grant long-time fans a bountiful gift with Fragments, offering up the rare opportunity to hear what it sounds like in the mixing booth as producers and engineers sift through the music and make a record. And, really, that’s the ultimate beauty of Fragments: It captures the many nuances of forgotten gems like “Mississippi” and “Standing in the Doorway,” presenting them in the same raw and pristine form in which Dylan first heard them.

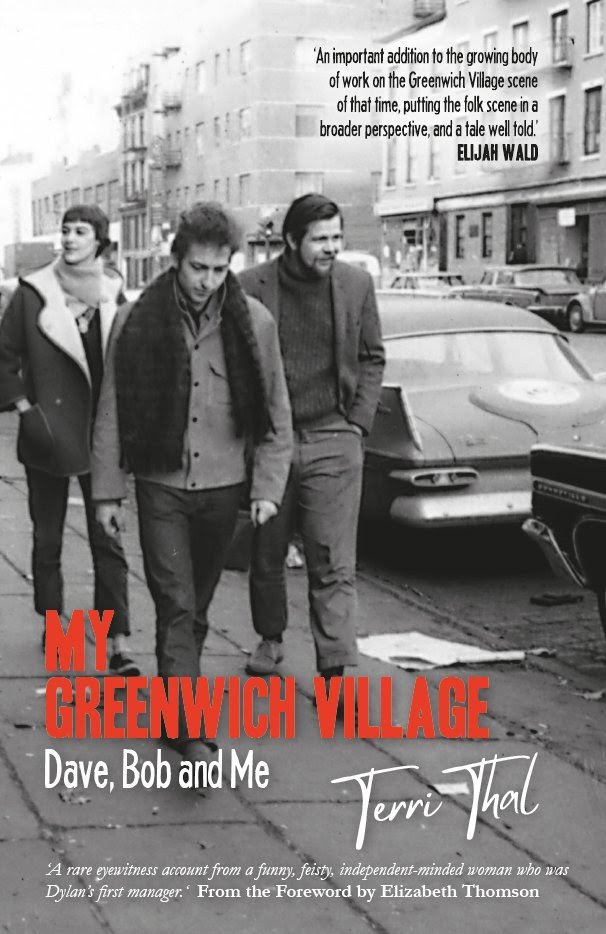

MY GREENWICH VILLAGE: Dave, Bob and Me. Terri Thal. McNidder & Grace.

Bob Started to come to our apartment, and he became a friend. For the first few months after he came to New York, he slept in people’s houses: Eve and Mack McKenzie’s, Sid and Bob Gleason’s. Camila Adams’, and ours. He was an easy guest to have around. Slept on the couch. Ate whatever I produced. And ravished our bookcases and record cabinets.

Page 133

I’ve read and heard a lot about the so-called competition between Phil Ochs and Bob about who was a better songwriter. If there was a competition, and I think there was, it was one-sided. When Bob started to write songs he wasn’t competing with anyone. “I’m not trying to be better than anybody,’ he once said to me. ‘I write what I see…’

Page 135

“Somewhere in my left-wing travels after Dave and I started to live together in the summer of 1959, I became friendly with a Trotskyist whose political name was Jack Arnold. Jack adopted Dave and me, telling us repeatedly that we would wind up in the Trotkyist movement. He became one of the people who were likely to be in our apartment any evening, and we argued politics incessantly.

Page 153

Terri Thal, who was married to folk icon Dave Van Ronk, was also Bob Dylan’s first manager, guiding the young singer in those early days before he signed on with Albert Grossman. In a quick blink, this book brings us back to Greenwich Village circa 1961, telling the inside story of the folk scene and beat cafes. Initially, My Greenwich Village introduces us to the young Dylan and allows us to begin understanding the complex relationship he had with the older musicians who helped him shape his own voice. But don’t be misled into thinking that this incisive, sometimes-blunt story is only about folk music legends; it’s also about Terri Thal: An activist and writer who was brave enough to step forward as an early Greenwich advocate for social change and creative expression. Obviously, these traits attracted both Van Ronk and Dylan and the two singers ostensibly gravitated to her as a counter-balance to their own points of view. In this sense, Thal likely appeared to Dylan as a more worldly version of Suze Rotolo, showing him pieces of everything a woman could be. If you’re interested in discovering where Dylan found his inspiration in those foundational years, Thal’s My Greenwich Village offers a relevant stepping stone.

End Notes

A wide array of photos, including a shot of a handwritten note from Dylan to Thal on the rear jacket of his first record, augment a captivating story. Along with Suze Rotolo’s 2009 memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time, My Greenwich Village writes the most interesting third-person exploration into Dylan’s early days in New York that we have to date.